Thrilling Talks: Giving Client-Winning Talks At Major Events

The bar to being seen as a good public speaker is pretty low - alas many people still fall significantly below it (and don't realise it).

Hi, I’m Richard Millington. Welcome to my consultancy newsletter. Subscribe to my newsletter to discover our systems for scaling your consultancy practice to $1m+ in revenue.

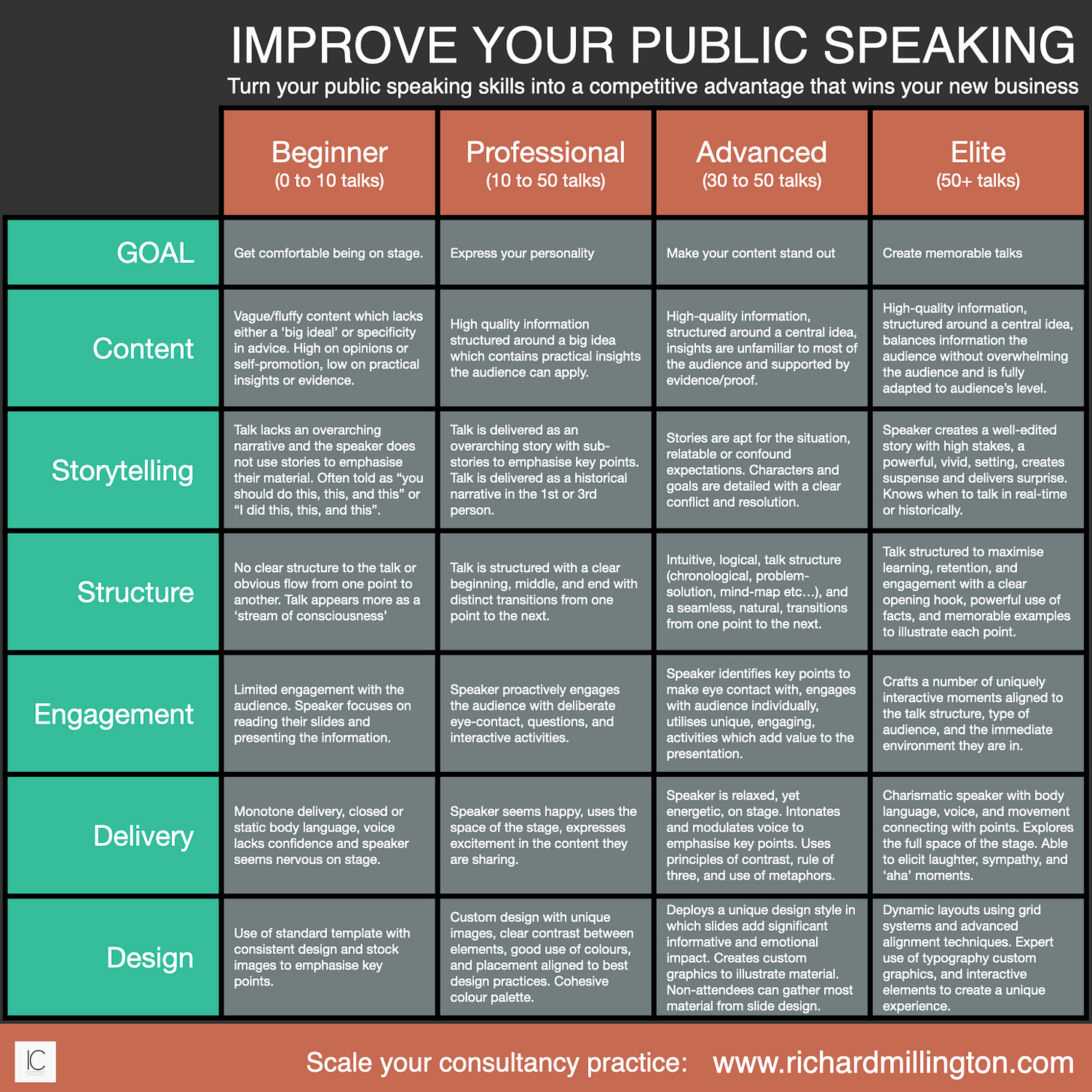

TL: DR—Too many consultants are just good enough at public speaking to get through a talk without doing anything embarrassing. But not good enough to give talks which attract clients or stand out in a speaker line-up. This will change if you deliberately focus on improving a skill each time you speak.

Leverage Points

One of the best leverage points for attracting new business is being better at something than others.

There are plenty of ways to do this, but if you’re in the consultancy space, I suggest considering public speaking as one of your leverage points.

If you can get good at public speaking - as in really good - where everyone else is average (or worse), then it leads to lots of discussions like this: